I have a friend who works for The Globe, they shall remain nameless, but part of their role involves having conversations with audience members and donors about the quality and content of the famous Shakespearean theatre’s productions and program schedule. Some of these conversations are not easy.

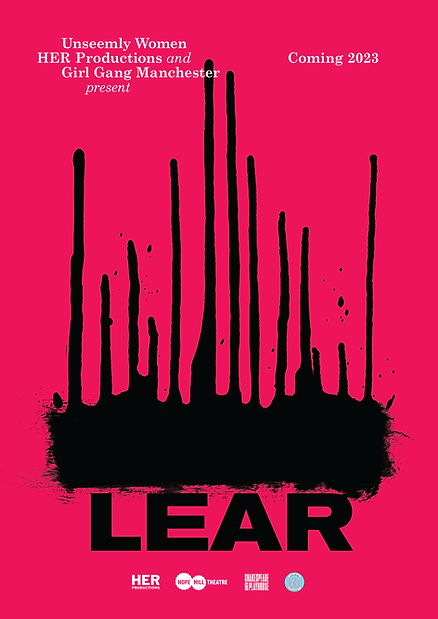

King Lear and the magnificent messiness of all-female Shakespeare

In 2019, I saw The Globe’s productions of Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, and Henry V. The trilogy starred Sarah Amankwah as young Hal becoming Henry V, and her energy was mind-blowing. I sat in on a rehearsal and inadvertently became the only audience member to whom she could address a speech. It was mesmerising… and a bit terrifying. The two other leading characters of the series were also taken on by females; Helen Schlesinger invited the whole audience in on every joke with skill as Falstaff; and Michelle Terry brought such clarity and reality to the lines and action of Hotspur, that I learned a thousand new things with every speech. Terry is also the artistic director at The Globe and, I think a little controversially, enjoys placing herself in main roles. When I saw her performance as Hotspur, though, I thought…fair enough. She has followed on from another slightly controversial artistic director in Emma Rice, who was criticised for installing modern lighting and sound rigs in the Tudor-style playhouse. But both women seem to have placed experimentation and ultimately play, at the centre of their approaches to Shakespeare.

The surprising, or maybe not surprising, thing about my conversations with my friend (after seeing the trilogy and fully enjoying myself) was that some people hate female-led Shakespeare. The choice to cast women in lead roles, and particularly in Sarah Amankwah’s case, black women, in ‘male’ roles, was very unpopular with some of the audience and funders of the theatre, and my friend had to listen to them complain, and threaten to remove their money every day. It made me start to think about female Shakespeare, deviation from the text, and even the rewriting or re-imagining of fiction in general. What makes anyone think they have a monopoly over stories? Why does the general public believe that there is a ‘proper’ way to represent these cultural, historical, and allegorical tales that Shakespeare himself was rewriting and re-purposing for his moment?

There are so many reasons why a director might choose to cast a Shakespeare play with gender fluidity, gender reversal, or gender neutrality. One of them simply being that there are good roles and women and non-binary people who want to play them. Some of the main roles in Shakespeare have such amazing meaty subject matter and speech – news just in, women want to be the main characters, and we don’t necessarily think about them as men, just interesting people to whom we can also relate. Other reasons might be more especially ideological or artistic; making a comment about the treatment of women in the play or now; questioning stereotypes; or confronting inequality.

Some circumstances make immediate sense, and some instances are more complicated – in Twelfth Night, for example, where Shakespeare is already playing with gender norms to create drama. But even in these circumstances, gender is worth playing around with – as in life! In almost every case, the ‘alterations’ add a million different dimensions to the meaning and to the melody of the drama.

While sitting in on HER productions rehearsals for LEAR as Girl Gang’s representative, lots of new things about the story started hitting me specifically because of the production’s commitment to a female and non-binary cast. Fresh feelings and new thoughts – all down to hearing a new voice speak Lear’s lines. It struck me how powerful it is to have Lear as a mother, played by Christine Mackie, removing love from her daughter Cordelia, played by Ella Haywood, as a punishment. Not that this takes away the impact of a father doing the same, but rather that for our cultural normal – where we are not all royalty/landed gentry and dependant on patriarchal inheritance money, but where we generally recognise that parental and often maternal love is a major motivating and manipulating factor in our lives – to have a mother disown a child is big.

Hearing her say ‘Here I disclaim all my paternal care’ after flexing a bit of emotional bribery; ‘thy truth, then, be thy dower’, really packs a gut punch. Cordelia’s mother is saying to her, you haven’t said the right things to me, and so I disown you, I won’t speak to you anymore.

In the same vein, it is perhaps more inherently powerful, and spiteful, to see a mother pronounce sterility on her daughter, as Lear does with Goneril, than a father. When Lear wishes to ‘Turn all her mother’s pains and benefits/ To laughter and contempt, that she may feel/ How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is/ To have a thankless child!’ in this production, it will invoke ideas of inherited female trauma, made sharper by the characters’ shared sex. It struck me also that Lear’s descent into chaos here might play as the beginnings of dementia. As a disease twice as likely to affect women than men, Alzeihemers will have touched many female family members of the audience, if not themselves. Cordelia asking of Lear ‘Sir, do you know me?, and the reply: ‘You are a spirit, I know: when did you die?’, brought to my mind the image of a mother forgetting the face of her daughter as she visits in a nursing home.

This is my interpretation, and not necessarily dictated by the artistic intention behind HER, Girl Gang, and Unseemly Women’s all-female casts. Sometimes it can be just because women and non-binary actors are incredibly talented and it is a joy to put them on the stage together. The cast of LEAR is asked by director Kayleigh Hawkins to consider characters on a gender spectrum from masculine to feminine and to tentatively begin to place themselves on this spectrum as they begin to interpret their roles. Nothing is mandated or fixed though, as in life, and decisions can be made late, after a lot of play in the room. That is a word that we need to keep returning to – and perhaps reminding the angry Globe audience members on the phone if – it’s a play; it’s a game, and it’s meant to be messed about with. When we stop playing with it, like a neglected puppy, it dies – or at least gets very, very sad. Kayleigh points out that the overwhelming feminity of the group will of course impact the way this production goes, but that’s not what it’s ultimately about, it’s about how talented everyone in the room is.

It can be complicated though, as a decision in the rehearsal room is made not to change pronouns – the edited text won’t be edited in that way. When I played Hal in a production of Henry IV Parts 1 and 2, we decided that I would be ‘her’ and ‘she’ but not ‘princess’. We kept ‘prince’ because it, unfortunately, sounded simultaneously insipid but also with the potential to be stronger, more military. Although, on reflection, it might have been more powerful to identify with a Diana than an Andrew…

As the LEAR cast starts to untangle who they are and where they are, the discussion becomes about the specificity of character and circumstance, rather than reverting to stereotypes. Kayleigh says, ‘Basically you’re not all playing blokes’. The actors are playing people, human beings, in a world that they are building together through the rehearsal process.

There are many more reasons to make female Shakespeare, more examples to give of female-led productions and so many practical and intellectual things for a company like HER to make decisions on – things that are specific to the type of work they want to do and most importantly the text of Lear itself. It’s a complicated process with millions of different combinations of choices that all have the potential to make beautiful and meaningful art. That’s why the dissenting voices are so baffling. I’ve seen and been in shows where gender playing works, and ones where it doesn’t. But that’s ok. There isn’t a finite amount of Shakespeare – there is plenty to go around. Experimentation like Rice’s, Terry’s, and HER Productions’ simply adds more and more threads to an ongoing narrative. We’re weaving a tangled web, and that’s…good! Anyway, they can’t stop us. It’s happening, the writing is there, it’s publicly available and the words can be anyone’s and everyone’s. As Christine commented in an interview with BBC Radio about the production, ‘There’s room for different voices saying these lines.’